The lyrics caught my attention. It was a quiet day in the archive and a volunteer asked if she could play the Hamilton soundtrack. As a history buff, I’ve been fascinated by the musical since it hit Broadway. But on this day, it was one song in particular that spoke to me: “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story.”

The notion of the pitfalls of legacy resonated with me. Who tells your story when you’re gone? Who interprets your story? What happens when you’ve erased yourself from the narrative?

Too often we rely on our descendants to keep our story alive, but what happens when your family line ends? Who will keep your contributions to this world from fading out of existence?

The answer is often laid on the shoulders of archivists, whose job it is to preserve history. And, when there is no one else to do it, to share the stories hidden amongst hundreds of boxes.

Take, for example, Carrie Sittig Cohen. Ever heard of her? Probably not. She was born and raised in Detroit and died in 1936. It’s unlikely anyone in Detroit has heard of her either. Yet, Cohen’s bequest to the United Jewish Charities (UJC) was the largest one ever given to a Jewish philanthropic organization in Detroit at the time (made even larger when it was combined with her brother’s own bequest in 1937). It was a record-making gift that stood for nearly two decades. The combined gifts of $500,000 would have been equivalent to $8.7 million today.

Cohen was posthumously recognized for her philanthropic service when she was named to the Outstanding Jewish Women of the Year list published by Eve Magazine in September 1936.

But despite being an heiress, we know little about Cohen; even her image is elusive. We don’t know where (or if) she attended school. The census records indicate she never worked, nor is there evidence of her community involvement. She never married and never had children. Her direct line is gone.

And yet, her prolific family can be traced back to two founding Jewish families of Detroit and Ann Arbor.

When Cohen’s paternal grandparents, Marcus and Betsy, brought their family to Detroit, the city had a population of about 20,000. Of this 20,000, only 51 were Jewish. But that was enough to start a synagogue, and in September of 1850, the Bet El Society (today called Temple Beth El) was formed. Marcus conducted the religious services until a rabbi could be engaged.

Cohen’s maternal grandparents, Judah and Marie Sittig, emigrated from Bohemia. In 1845, they traveled to Ann Arbor, Michigan and were among the earliest known Jews in the area. The Sittigs eventually moved to Detroit, where their daughter Rose would meet Simon Cohen.

Carrie Sittig Cohen, born in 1877, was the last child born to Simon and Rose. The details of her childhood are sparse. She was one of four siblings, although only three lived to adulthood. The family lived in an affluent area of Detroit, always with live-in help. The city directory lists a variety of occupations for her father: retail milliner, clothier, insurance agent. Cohen’s brother Solomon was a lawyer while her other brother Joshua dabbled in areas as diverse as soap salesman, travel agent, and merchant.

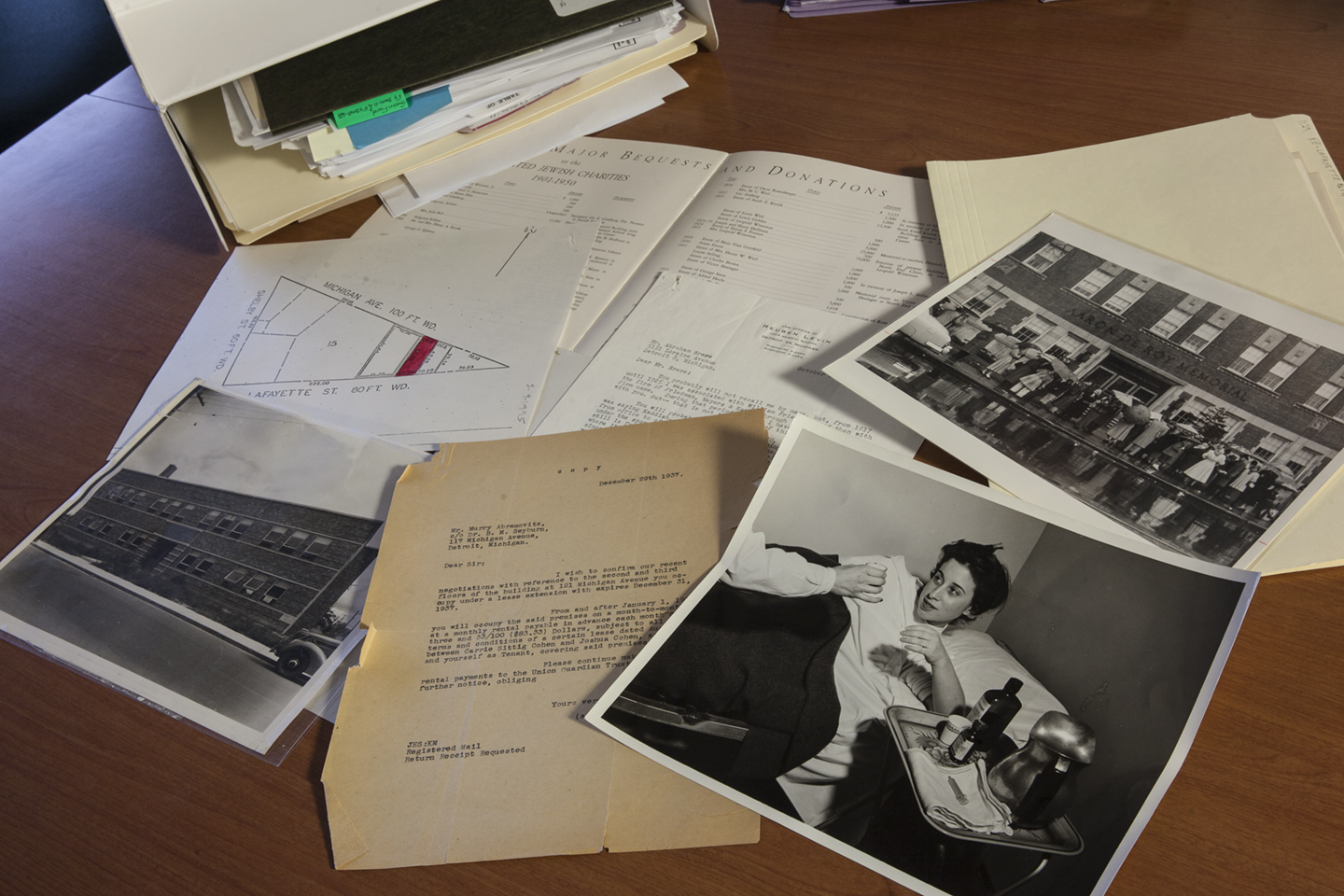

It is assumed Cohen’s wealth was inherited. In addition to her monetary assets, she owned interest in more than six real estate properties. All the property she owned was included in her bequest to the UJC. Many of the properties came with tenants, including a triangle-shaped building at the corner of Michigan and Lafayette Avenues in Detroit, which included what the paperwork referred to as a “hot dog place.” The restaurant, which still stands today, is well-known among all Detroiters, as well as viewers of programs such as Man v. Food and Food Wars. Because that “hot dog place,” is a Detroit cultural landmark. Two competing family businesses, side-by-side, called American Coney Island and Lafayette Coney Island.

The Carrie Sittig Cohen Fund touched much of Detroit’s Jewish community. Its proceeds helped pay for an addition to Fresh Air Camp to care for sick children and administer health exams. It paid for a new school for 500 students named the Rose Sitting Cohen Building. It helped pay for a new Jewish Community Center. Other agencies touched by Cohen’s generosity included the North End Clinic and the Jewish Home for the Aged.

When the Jewish community migrated out of Detroit into the suburbs, the buildings Cohen helped finance were abandoned. Her fund ran dry. Even her portrait that supposedly hung in the Jewish Community Center was lost. What little we knew about her was buried.

In fact, her name was only unearthed by coincidence. A volunteer was processing a collection of real estate records and came across a folder about the property at Michigan and Lafayette Avenues. Both of us being native Detroiters and hot dog enthusiasts, we jumped on the opportunity to learn how this property had fallen into UJC hands. It took weeks of research to trace the building to Carrie Sittig Cohen and ongoing research to uncover any information about her life and legacy.

There are endless tales hidden in an archive, just waiting to be discovered. As an archivist, I am lucky to play a role in bringing the past to present. By preserving historic documents, we preserve the legacy of people like Carrie Sittig Cohen. And maybe one day, the story a future archivist uncovers will be yours