It’s a story Scott Kaufman, Federation’s Chief Executive Officer, likes to tell, particularly as he leads first-time visitors through Yad Vashem – the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem.

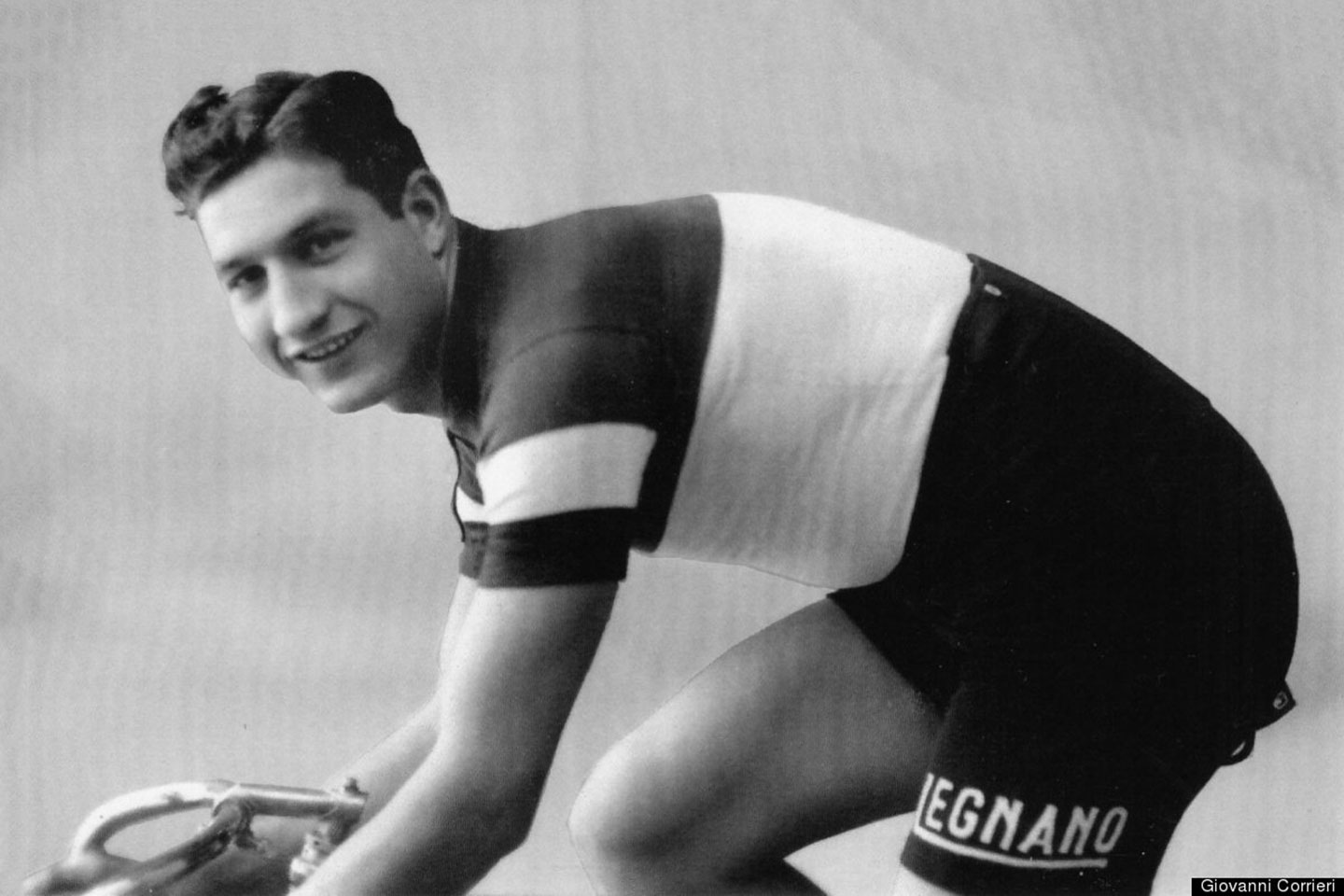

It’s the story of Gino Bartali – winner of the 1938 and 1948 Tour de France – and recently celebrated in Israel as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

As everyone who travels with Scott knows, he’s an avid cyclist with a particularly Jewish frame of mind. It was early in October, a week before Scott was scheduled to take twenty Detroiters on a Federation mission to Poland and Israel. Checking racing stats online to see who won the World Championship Race in Florence, Scott stumbled upon an article about Bartali and learned how he helped rescue Jews in his native Italy by hiding forged documents and papers in the tubes and seat of his bike.

“I had heard something about this cyclist before, but somehow on the Mission, Bartali’s story really started to resonate with me,” says Scott.

First stop: Poland

In Krakow, the group visited an old pharmacy in the Jewish Quarter where there was a small museum to honor a pharmacist who had saved Jews during the war by forging documents and smuggling medicines. “Standing in that little pharmacy,” Scott says, “I found myself talking to the group about what it means to be one of the Righteous Among the Nations. You had to have saved lives, not have taken money for your actions and you had to have put your own life at risk. And as I’m explaining this, I mention that I had just read about Gino Bartali, and I shared his inspiring story.”

On Federation missions there are always moments of discovery for which no one really prepares. They just happen, thanks to quick thinking tour guides.

As Scott describes, “On October 10, three days after the encounter in Krakow, we were at Yad Vashem. All but two of the group were with me in the museum on a first-time tour. Because Carolyn Bellinson and Jim Aronovitz had toured the museum before, they took off with a separate guide to visit the surrounding grounds where they found a ceremony about to begin –honoring Gino Bartali! Since only the guides have access to phones inside the museum, their guide called our guide – advising us to hurry outside, to the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations. And there we were, with dignitaries and TV crews from all over the world, to witness Bartali’s induction at Yad Vashem. An event we’ll never forget.”

What were the chances?

“What were the chances of being there on that day, at that moment? The experience was a once-in-a- lifetime happenstance,” says Jim Aronovitz. “While Carolyn and I were on an Art and Architecture Tour of the museum, we strolled into the Garden where they were setting up chairs for an event in front of a covered plaque to be presented. The people there were speaking Hebrew and Italian, but fortunately our guide learned that Bartali’s family was there to accept the honor for their father. At the ceremony, the story which Bartali’s son told really struck a chord with me. He said that one day his father Gino sat him down and told him about what he had done during the war. He told his son that it isn’t important that people know the good that you do, just so long that you do good deeds for others. His son then asked, “Then why tell me what you’ve done now?” Gino answered, ” Because one day my deeds will be very important for everyone to know and remember.”

The Gino Bartali Story

Excerpted from an essay based on the book Road to Valor: A True Story of WWII Italy, the Nazis and the Cyclists Who Inspired a Nation, by Aili McConnon and Andres McConnon.

Gino Bartali is best known as a cycling legend who holds the record for the longest time span between victories at the Tour de France – ten years – a feat made all the more impressive by the Tour’s status as one of most grueling endurance competitions in the world and the fact that Bartali was an old man (by cycling standards) when he made his comeback in 1948.

Born in a poor town near Florence in 1914, Bartali grew up in a world of grinding poverty. With few career options, Bartali dedicated himself to cycling: from sunrise to sunset, he rode around the Tuscan hills and built up his physical endurance.

Bartali’s relentless training paid off, and he made a meteoric rise in the cycling world, turning professional only a few years after his first race.

Then cycling took the one person dearest to him.

Bartali’s younger brother Giulio, also a gifted cyclist, was killed in a racing accident. This loss devastated Bartali, as he had encouraged Giulio to begin racing in the first place, and led him to quit the sport.

Bartali, a devout Christian, turned to prayer as he wrestled with grief. When he finally made the difficult decision to return, Bartali funneled his sorrow into a new motivation: he would race to honor the memory of his brother.

With his innate ability to tire out rivals, particularly in the mountains, Bartali started winning races again. In 1938, at the age of twenty-four, he won the Tour de France.

And then it all fell apart again.

Relations between Italy and France deteriorated, and Bartali was barred from returning to defend his title at the 1939 Tour. When war broke out in Europe, Bartali could no longer compete and was conscripted into military service, where he worked as a military bike messenger in Tuscany and Umbria.

When the German army took control of Italy in the fall of 1943 and Jews began to experience the full terror of the Holocaust, Bartali was asked to join a secret initiative to help save them.

Few requests could have carried a heavier burden. With the collapse of his career as a top cyclist and the transformation of his beloved country into a nightmarish and dangerous place, he feared for his wife and two-year-old son. It would have been easier – and safer – not to get involved.

But he chose differently.

Risking his own life, he sheltered a local Jewish family in an apartment purchased with his cycling winnings. He also began to smuggle counterfeit identity documents around Tuscany and Umbria, enabling numerous Jews to conceal their true identities and avoid deportation to a concentration camp.

Bartali returned to the Tour after the war and found that physical endurance alone would not bring him success in an event where most of his competitors were now ten years younger than he. It was his mental resilience that would power him to win, not only for himself, but also for all of his Italian countrymen.

Even as Bartali reached the peak of his sport, he never lost sight of the fact that it was his inner strength that carried him through the most difficult moments of his life. As he would tell his son Andrea, “If you’re good at a sport, they attach the medals to your shirts and then they shine in some museum. That which is earned by doing good deeds is attached to the soul and shines elsewhere.”

Gino Bartali died in 2000 and rarely spoke about this for all his years. His son Andrea Bartali led the effort to gain recognition for what his father did.