by Vivian Henoch

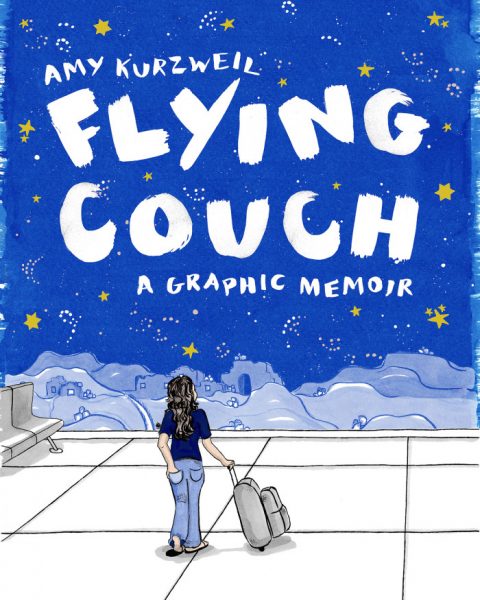

Don’t let the comfy book title or its starry-eyed cover mislead you . . . Amy Kurzweil’s Flying Couch: A Graphic Memoir is a masterwork – all the more notable in the fact that its author was only 29 when the book was published with critical acclaim including a New York Times Book Editors’ Choice among the Season’s Best Graphic Novels of 2016.

“Novel” is an apt description for Amy’s inventive narrative – a story that gently unfurls, takes flight and grabs the reader along on her search for Jewish identity and journey of discovery.

Amy’s narrative arc would be dizzying, were it not for her comic touch and steady hand as the Artist weaving fragments of childhood memory and the heroic life stories of her mother, Sonya, The Psychologist, and her grandmother, “Bubbe Lily,” the irrepressible Holocaust Survivor.

To borrow a line from the pop rap musical Hamilton, “Immigrants … we get the job done.” Amy’s struggle and triumph in Flying Couch is a testament to the strength and resilience of her grandmother and mother, survivors coming to America, adapting, assimilating and adding their voices to the music that leaps to the pages of Amy’s writing and illustrations.

For Detroiters, Flying Couch has a charming local appeal. “Bubbe” is Lily Fenster, 92, matriarch of a small family with roots in Huntington Woods and Franklin. Lily now lives in Birmingham, MI and Naples, Florida. She and her husband, Grampa Dave, raised their family in Oak Park and Bloomfield Hills. Lily’s testimony was recorded in 1994 in an interview with Dr. Sidney Bokosky and is stored in the Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive at the University of Michigan-Dearborn Mardigian Library with copies also in the archives of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington.

With fond memories of family pilgrimages to her grandparents’ home in Bloomfield Hills and walks through Cranbrook Gardens, Amy now lives in Brooklyn and teaches writing and comics at the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan. Sonya, a graduate of U of M, is the Founder and Director of the Sonya Kurzweil Development Center in Boston and a Clinical Instructor in Psychology at Harvard Medical School.

At a book signing event held in May at the Holocaust Memorial Center in Farmington Hills, the three women came together in a rare opportunity to share their stories.

Meeting Lily in the Lobby

There was a window of 15 minutes before the presentation – the time we had appointed for pictures with the Fenster-Kurzweil family – when I spotted Lily, elegantly dressed for the occasion and clearly enjoying the celebration around her granddaughter’s book. With a break in the gathering that had surrounded her, I stopped to say “hello” and introduce myself as the writer from the Jewish Federation.

Perhaps it was the recorder in my hand, but it took only a moment for Lily to launch into her story – back in time to the Warsaw Ghetto in a rapid-fire trance – a litany of detail, the intensity of which I have seen before in the testimonies of other Survivors.

Thinking I had my recorder cued up ready to go, I inadvertently hit pause. And so, it happened that Lily Fenster’s words were recorded only in my memory in broken shards and images as she described her once beautiful blonde braids and recalled a hunger so desperate for a crust of bread – a crust of bread she repeated – telling me how her three-year-old sister died in her arms . . .

Lily’s words were chilling, but her voice was warm and tender, and her eyes danced around the room, so filled with light and life. . . Five minutes seated in the lobby in the Holocaust Center with Lily Fenster turned out to be a far better introduction than I expected for a “book talk” aboard Flying Couch, a Holocaust story worthy of reading and re-reading for generations.

Excerpts from the program follow:

In Sonya’s words

“Aptly named for a journey of discovery embarked upon in a place of safety, comfort and support—my daughter Amy tells a story about our family . . .”

It’s an American story, a World War II story, a Holocaust story – about refugees and immigration, trauma and resilience—all things this museum [the Holocaust Memorial Center] and its friends know a lot about.

It’s also a story about coming of age and coming of identity—in Amy’s case she comes to identity as a serious female artist. Flying Couch also inspired a transformation in my identity.

Raised in safe, comfortable Newton, MA, it never occurred to me that she’d be captivated by my mom’s Holocaust story. As a psychologist who prizes stories, I’m surprised to think about that now.

Like many Holocaust survivors, I tried to avoid thinking about the Holocaust. I found my parents’ war stories to be unimaginable, never-ending nightmares.

Full disclosure, I was born in DP camp in southern Germany – Ellis Island Class of ’51—the first person in my family to graduate from high school. We immigrated by ship. I was four years old. The voyage took two weeks on a ship used for cargo during World War II.

Pulling into New York Harbor, I remember being thrilled to be outside on the deck of the ship for the first time in weeks. I remember being impressed to see the Statue of Liberty and having been told that I should cherish the moment. And I still do.

In Amy’s words

This event is a homecoming for me. I have fond memories of visiting Detroit — visiting Bubbe in her house in Bloomfield Hills. I remember that home as a place filled with memories —photos and knickknacks that I felt attached to – a place filled with food and family and of course [all those things] we protect and take care of.

Our story is about home. I started this book when I left home for the first time and I tell of Bubbe’s experience leaving home for the first time. Flying Couch ultimately is my story about finding and reclaiming home for myself.

“Bubbe once said something really smart about my book: she said I wanted to feel what she went through. Not just understand it, but feel it.”

I grew up safe and comfort able In the American suburbs. My life by comparison to my mother’s life and my grandmother’s life was very easy. I didn’t grow up with the hardships they experienced.

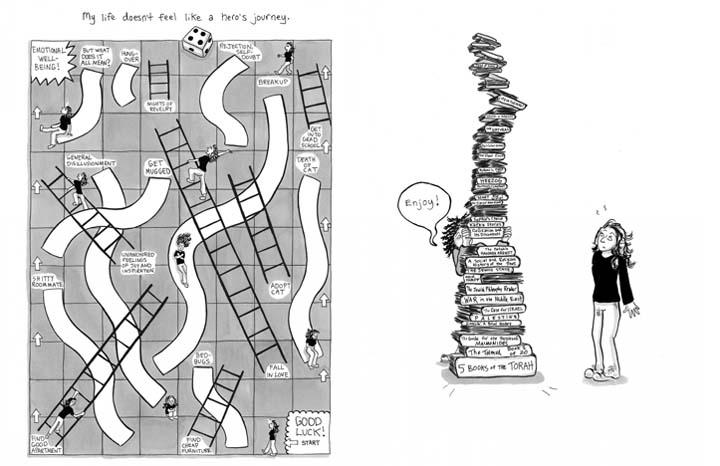

But I was a sensitive kid. I had curiosity, compulsions, neuroses and anxieties that are funny in retrospect.

With my mother’s support, I usually was all right. But in my transition to college at Stanford, I felt sick with anxiety . . . The irony of my young adult life was that my mother had taught me so much about how to deal with my natural sensitivity, but the one thing she had not taught me how to do was to leave her.

I didn’t know why leaving home was so hard for me until my mother gave me the transcript of my grandmother’s interview. I always knew that Bubbe was a survivor, but I hadn’t thought to connect her experiences to anything that had to do with me in my own life until I had the whole document in front of me and read it like a story.

Reading her story, holding it, seeing her voice on the page, it became clear to me that so much of my anxieties of leaving home had their roots in this story, with my grandmother’s first traumatic loss of her home and her family.

The grief and the fear that she felt, my mother felt too. These were emotions that we all shared.

In college, I decided if I could take these stories, be faithful to my grandmother’s voice, and invest her stories with my own creative projections, then I might start to integrate myself with this history rather let it haunt me. If I could invest myself in these stories as their creator, I might feel entitled to the emotions surrounding them and, by proxy, entitled to the fortunate life that everyone has worked so hard to give me.

In this way, I became the protagonist of my own story.

Praise for Flying Couch

Beyond its notice in The New York Times, Flying Couch is a Junior Library Guild Fall 2016 Selection, listed in Kirkus Review as one of “The Best Memoirs of 2016, named by Young Adult Library Services Association as one of 2017’s “Great Graphic Novels for Teens” and Foreword INDIES Award Gold Medal Winner for 2016.

Have some fun watching the book trailer here.