A Life in Letters

By Vivian Henoch, Editor myJewishDetroit

September 1, 2014

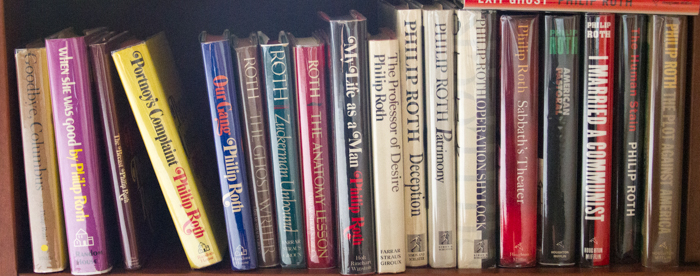

How is it possible to retire from an acclaimed writing career? Well, if you were Philip Roth you’d publicly announce that you have stopped writing. That’s just what Roth did. In 2012, the Pulitzer Prize winning writer announced his retirement from a luminous career. He told media outlets that he would not write another word of fiction.

Prior to Roth’s retirement, he re-read novels from authors like Hemingway and Dostoyevsky, as well as most of his own body of work. “I read all the great stuff, and then I read my own and I knew I wasn’t going to get another good idea, or if I did, I’d have to slave over it,” Roth said in an interview with The New York Times.

The then 80-year-old Roth was unequivocal about his retirement. A note on his computer reminded him “the struggle is over.” In 2013, Roth silenced skeptics when he reaffirmed his retirement to the online U.S. edition of theguardian. He said he was “spending his days swimming, watching baseball and nature-spotting.”

The controversial place Roth holds in the Jewish and literary communities is universally recognized. Some find his depiction of Jewish characters as vile. Others view him as an American novelist, who, like many writers, drew on pieces of their own lives to stoke the creative fires vital to crafting good work. Whatever the case, the public reaction to his retirement inspired me to read Roth.

On first reading Portnoy

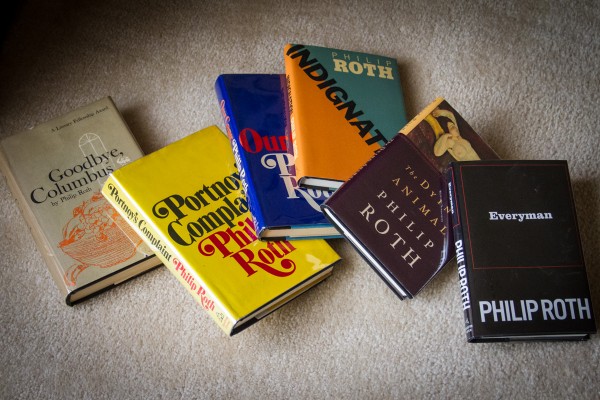

Portnoy’s Complaint was a first attempt to grasp Roth’s work. It affords the reader an opportunity to be a voyeur during a session with a psychiatrist that explores the brilliant, but tormented mind of Alexander Portnoy. From his bowel movements to his sexual obsessions, Portnoy takes us on a wild ride. His musings are hilarious, sad and manic. Beginning in early childhood, Portnoy admits that his every waking moment dwells on his obsession with his mother

The first woman of significance in his life manifests herself everywhere. The young Portnoy says, “she was so deeply imbedded in my consciousness that for the first year of school I seemed to have believed that each of my teachers was my mother in disguise.” All of this boy’s relationships with women would be forever tainted by his mother’s omnipotent presence.

Is it the quintessential stereotype of the Jewish mother that drives Alexander Portnoy to express a disparaging view of his Jewish upbringing? Or are Alexander Portnoy’s neuroses indicative of his inability to reconcile his place as a Jew in a non-Jewish world? Readers can draw their own conclusions, or perhaps there isn’t one.

Everyman, a study in contrasts

Next was Everyman, Roth’s 23rd novel published in 2006. In addition, it was honored with the PEN/Faulkner Award, Roth’s third. Initially, comparisons to Portnoy and Everyman, are hazy. Themes of death, disappointment and unfulfilled expectations run through both novels.

Everyman begins with the funeral of the nameless central character. The sparsely attended funeral is a clear sign that the man in the coffin lived a life that moved few to acknowledge his passing. Yet, Everyman’s narrator informs us that the protagonist lived life as a “reasonable and kindly, an amicable, moderate, industrious man,” a “square” who took on a moneymaking career to support his family.

Like Portnoy, an intimate look into a Jewish male’s mental travails persists. Unlike Portnoy, the central character does not attribute the sole cause of his jealousies, conflicts, pettiness and failures to his mother or his Jewishness. Neither does he fully accept the part he played in the setbacks that followed him throughout his life.

Marriage, children, a brother and parents who adored him failed to bring him peace. Rather than confronting his fragilities, he chose extramarital affairs, a career that aborted his real passion and suffered from strained connections with his sons from his first marriage. Only his daughter from his second marriage stands by him. Yet, she is more parent-like towards him than he is to her.

His body fails him. His hernia surgery, as a nine year-old, portends the future havoc his body will endure. A host of physical maladies follow him until, as a man on the cusp of his seventh decade, he quietly expires on the surgeon’s table. Undeniably fallible, he fears death, yearns for “shiksas,” lives recklessly. He throws aside those who fiercely love him.

Roth was relatively young when he wrote Portnoy’s Complaint. Not surprisingly, Alexander Portnoy is a confused young man attempting to shed himself of his self-imposed anguish. When Everyman was published, Roth was 74, close to the age of Everyman’s protagonist. Whether the novels reflect specific periods in Roth’s life is a question for one who has an intimate grasp of Roth’s work. One thing is certain; Roth’s novels are unlike anything I have ever read. American Pastoral will be my next read.

A book lover and avid reader, Linda Laderman is an area free-lance writer and can be reached at Linny4@me.com

Editor’s note: myJewishDetroit now welcomes readers (and writers) sharing book reviews, news and views on all things Jewish and literary. To post here, please contact Vivian Henoch, henoch@jfmd.org. To start or join the conversation on this post, visit Federation’s Facebook page.