Against the backdrop of suburban traffic along Orchard Lake Road in Farmington Hills, the building looms: imposing and haunting, if not an intentionally provocative presence. Through its doors, millions of visitors have come to learn, to reflect, to remember, to share stories that forever change lives. This is the Holocaust Memorial Center Zekelman Family Campus.

The last thing you might expect in a visit to the Holocaust Center is to meet a young volunteer with a German accent.

“Hello, my name is Richard Bachmann. . .

You may ask what I’m doing here. I am a volunteer at the museum for one year through the Service for Peace program of the German organization, Action Reconciliation Service for Peace.”

We take a breath and take in Richard’s words of introduction, noting first his impeccable English, then his handsome face and earnest smile . . . and we see that even in a museum, history comes down to personal stories. And those stories can take unexpected turns, both large and small.

Often called upon to meet visitors and speak to groups of school children at the Holocaust Center, as well as in the community, Richard Bachmann is one of 180 Action Reconciliation Service for Peace (ARSP) volunteers working around the world, including 22 currently here in the United States.

Richard explains, “In German, the name of our organization is Action — Sign of Atonement — Service for Peace — which has a distinctly different ring to it than the official English name. For over 50 years, ARSP has been the organizing instrument for young people from Germany ready to volunteer in countries and communities that have been harmed by Nazi Germany, especially by the Holocaust. Since 1968, in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, ARSP has sent more than 700 volunteers to the U.S. to support organizations pushing for social justice and to work with the Jewish community, the elderly or socially disadvantaged in projects undertaken by museums, shelters, community centers and schools.”

At 26, Richard is a graduate of the University of Leipzig, working on his Masters in American Studies. On staff at the museum through August, Richard assists with research, writing text and organizing events. In addition to working at the Holocaust Center, he visits Holocaust survivors and their families once a month at Café Europa, a program at Fleischman Residence and the JCC in Oak Park organized by Jewish Senior Life.

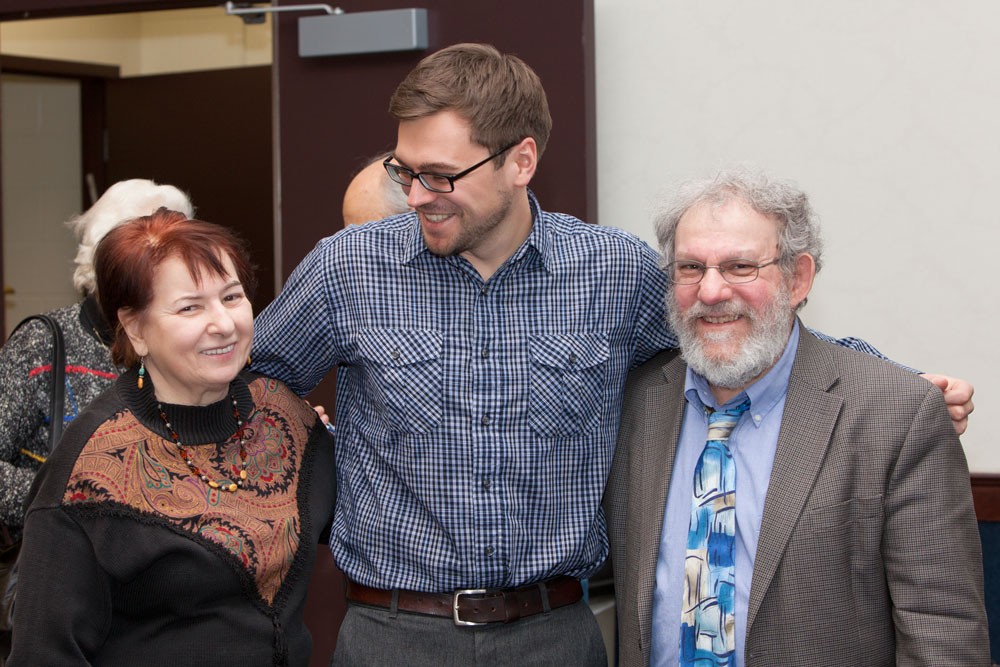

It doesn’t escape us that Richard’s work in the community must be as challenging as it is rewarding. As we chat together with museum director Stephen Goldman, it takes us no time to see how well suited Richard is to his role as an ambassador of good will in the community. Personable and thoughtful, he is candid in sharing his family background, his personal experience and motivation to do voluntary service in the Jewish community. As Stephen notes, “With Richard’s experience — and the depth of his thinking — we couldn’t have asked for a more knowledgeable and proactive Fellow from the ARSP program.”

A personal history

Richard speaks with the voice of a historian as he describes growing up in a countryside town in the East German state of Saxony, 30 miles from Leipzig. “I’ve always considered my home state beautiful,” he says, “but there was and still is a visible and active neo-Nazi movement there. I grew up with the realization that the violence and hatred of the past was not as far away as some people wished and believed it to be. Despite ardent efforts by the German government, organizations and individuals aimed to educate citizens on the crimes of Nazi Germany, despite mandatory Holocaust education in school, and despite trips to the memorials at former concentration camps, certain elements of Nazi ideology have managed to survive.”

Leaving home

Choosing to go to the University of Leipzig, one of Germany’s oldest and most prestigious schools, Richard claims, “I was ‘lazy’ — a typical kid — it was a good school, close to home and all my friends were there.” Two years into college, looking for more meaningful work during the summer, Richard applied for the Summer Camp program organized by ARSP and spent two weeks working and studying in Terezin in the Czech Republic at the site of the former Theresienstadt Ghetto and Concentration Camp.

Inspired by the cultural exchange of students in the ARSP program and the experience overall, Richard encouraged his younger sister, Theresa, to apply for a fellowship as well. She joined the program immediately following her graduation from high school and spent a year as an ARSP volunteer at the Holocaust Center Pittsburgh. “Her experience in Pittsburgh was very motivating for me,” Richard recalls, “I had a chance to visit her, and I’ll never forget the pride I felt seeing my ‘kid’ sister addressing an audience of 400 students at the University of Pittsburgh. Currently she is working on her Bachelor’s degree in Arabic studies at the Philipps University Marburg, learning Arabic and Hebrew and preparing to spend two semesters in Cairo.”

Richard’s year in Detroit marks his fourth extended visit to the U.S. In September 2010, while still an undergraduate, Richard participated in a workshop at the Wende Museum in Los Angeles. The project that he organized with five friends from the University of Leipzig brought him together with students from Loyola Marymount University to develop an online exhibit focusing on everyday life in East Germany between 1949 and 1990. In 2011 he was awarded a Bachlor Plus Fellowship from the Institute for American Studies Leipzig and spent two semesters at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio where he took courses in Intellectual History and was a fellow of the Global Leadership Center.

Sharing his story

Ask Richard what it’s like to be part of the third generation of Germans after World War II and actively working for an organization with the mission Never to Forget the atrocities of the Holocaust – and he shares both fond and troubling memories of his grandparents, born in 1926 and 1928.

“They were just children when the Nazis rose to power and in their daily school life they were educated in that ideology. They were encouraged to join the Nazis’ youth organizations where young German boys and girls would learn their roles in society: to be Good Germans.

My grandfather joined the army and in the summer of 1944, towards the end of the war, was drafted into the SS. Though he spoke little of what happened to him during the war and throughout his four-year imprisonment in a Russian labor camp, I am doing research in his Russian Prisoner of War records and am learning what he might have been involved in.

So, when I speak to school groups at the Holocaust Center now, I tell them about my grandparents, what their generation went through and the way they were educated and how their education affected them even after the war. I tell them that my grandmother is a very loving, open and kind woman, but sometimes some of the stereotypes she has in mind – particularly about the people of Poland – can be traced back to her education.”

Born after the war, now in their 40s, Richard’s parents are very supportive of their children’s graduate studies and what they do through ARSP. “But I don’t think they fully understand what we do,” observes Richard. “I have a degree in American Studies and I wrote my thesis in English, a language my parents only partially understand. Their world experience, growing up in East Germany during the Cold War, was so different from mine. Even today, their world is mainly centered around the East German countryside. And to some extent, they would be lost in my world.”

On Detroit

How is Richard Bachmann, ARSP Volunteer for a year, finding life in Detroit? “Inspiring,” he says. “What people do here is so exciting to me. I find that there are a lot of dreamers in the city. And, not only do they dream, they also have the drive to pursue their dreams. I don’t know if that spirit is distinctly an American thing or entrepreneurial in general. But in Germany, it seems to me that even when people are more politically radical, they ultimately steer to a very traditional way of life. Here people have the courage of their convictions.

Being here today, having this experience at the Holocaust Center — and meeting other young people who work in the city — specifically in downtown Detroit with organizations like Repair the World — and seeing how much passion they put into their projects — that’s really left me questioning: Do I want to be the guy who’s always in the library reading? And talking and talking? Why am I not doing this when I’m in Germany?”

On social entrepreneurism. What’s next?

At 26, Richard has seen quite something of the world. On an academic track, he can envision himself as a professor, but he too has a dream. “There’s theory and there’s practice,” he says. “My girlfriend and I are talking about starting an educational institute — a new model of higher education which is not as formal or exclusive as our system in Germany. In Germany, only about 30% of all secondary school graduates have the opportunity to enter a university.We’re talking about learning beyond the classroom, about bridging the gaps between academic life and the practical needs of people building personal connections and the basis for deeper understandings of one another. I guess in many ways, we’re talking about continuing the work at hand with Action Reconciliation Service for Peace.”